3.4.1 The issue of distribution

People in many parts of the world are starving or suffer from malnutrition although in purely numerical terms there is an adequate supply of staple foods. The main reason is not so much world supply as unequal access to food and lack of purchasing power. Conflicts and political instability continue to remain the key factors driving severe food insecurity. They lead to forced migration, interrupt production and trade and increase the risk of regional emergency supply situations. Extreme weather events and natural disasters exacerbate this situation, as do economic shocks such as inflation, currency devaluations and high import costs.

All these factors curb investments, weaken agricultural growth and hamper the establishment of strong institutions. Where state structures, infrastructure and market access are absent, the risk of famine is markedly higher. If overall conditions were better, a sustainable intensification of locally adapted cultivation systems could significantly improve regional supply.

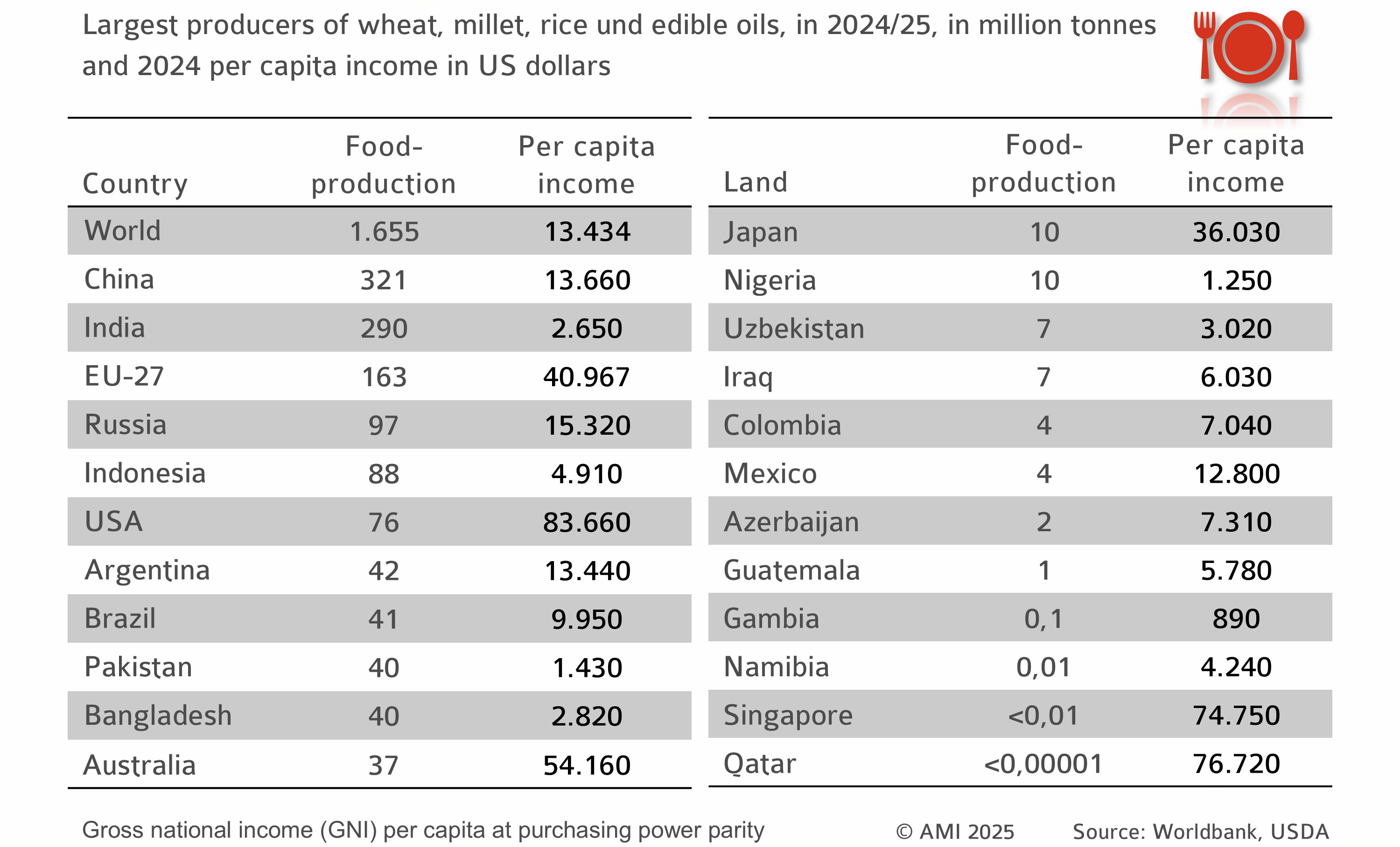

The international dollar, based on the US dollar, serves as the measuring rod for purchasing power parity (PPP). The range remains wide: whereas per-capita income in the EU-27 totalled around USD 40,967 in 2024, countries with high food production such as India and Pakistan reached only around USD 2,650 and USD 1,430, respectively. Income levels in states with very low purchasing power, such as Nigeria (USD 1,250) or Gambia (USD 890), are often insufficient for people to buy the amounts of food they need, although agricultural production does exist. Higher feedstock production for biofuels fundamentally increases global supply, but it does not solve distribution or income bottlenecks. Politically reliable framework conditions, functioning markets, and sufficient funds for crisis aid remain crucial – a “fuel or food” debate disregards these realities.

Distribution issue just one of multiple reasons

3.4.2 Food availability and climate change

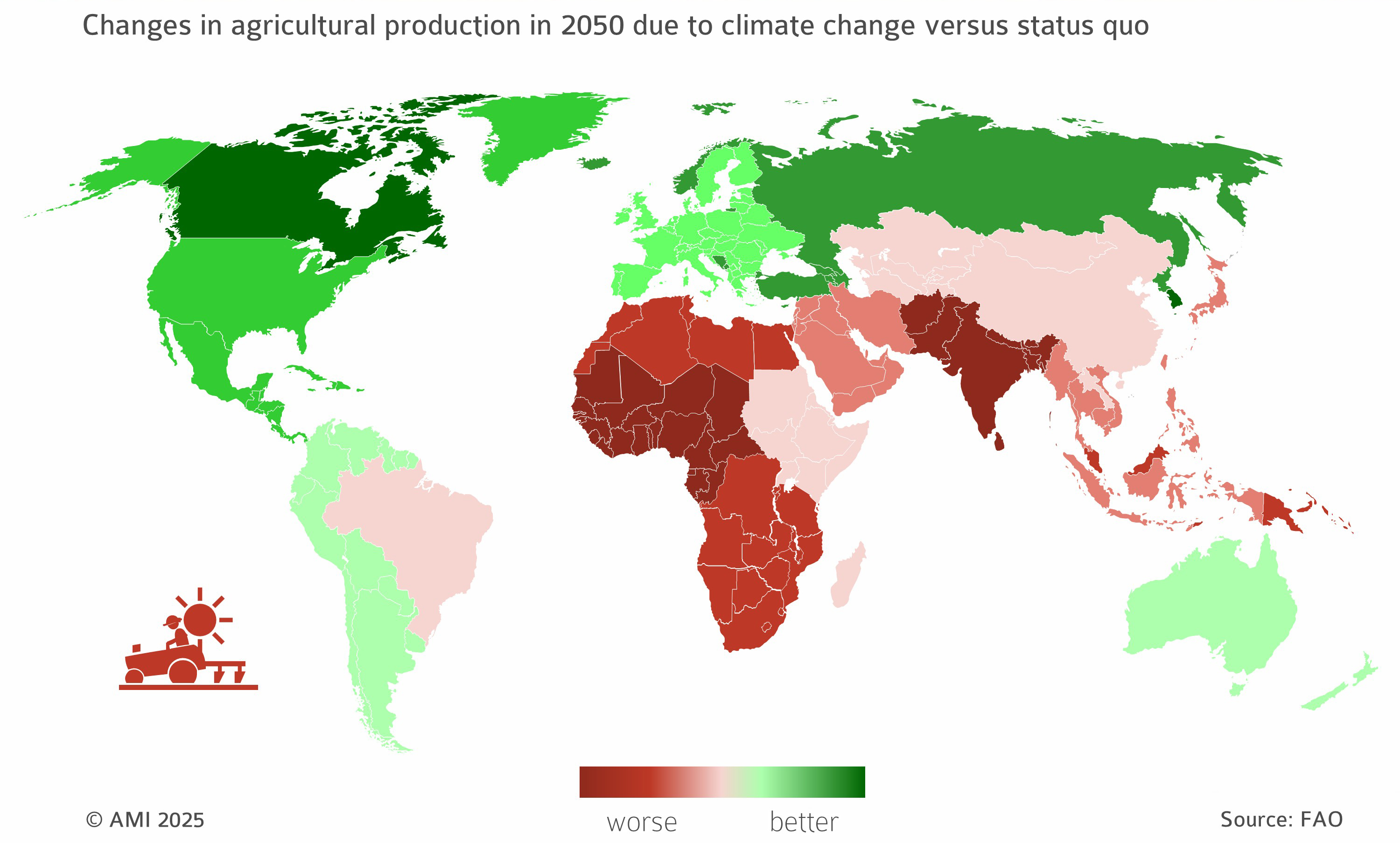

The implications of climate change on agricultural production are varied and differ between regions. Productivity gains are expected in some northern latitudes by 2050, while declines are anticipated in many tropical and subtropical regions.

The increase in greenhouse gas emissions is also driven by the conversion of forest and natural areas into arable land and plantations. The Amazon region and tropical forests in Asia and Africa are significant carbon sinks and crucial elements in regional and global water and precipitation cycles. Their protection is therefore part of international environmental policy and European regulations, examples being the EU sustainability requirements for biofuels from cultivated biomass and the EU Regulation for deforestation-free products.

Since global expansion of agricultural land needs to be limited, yields per unit area need to be increased through technological progress, sustainable intensification and resilient crop rotation systems. These include new breeding technologies to expedite the development of climate-adapted crop varieties. At the same time, access for small agricultural operations to innovative varieties, technologies and consultation needs to be improved, backed by education and training.

The implications of climate change are already taking their toll. In Europe, there are considerable regional differences. Whereas the south was affected by heat spells and forest fires in 2025, other regions benefited from mostly favourable growing conditions. Unequal access to markets, infrastructure, and technologies can further exacerbate climate impacts, widening the gap between industrialised and developing countries.

Changes in production due to climate change